Reflections on Friars Quay Part II: Pre-Post-Modernism?

To mark the 50th anniversary of the completion of the Friars Quay housing development in Norwich we asked our Senior Architect Matt Wood to reflect on the project. Click Here for Part I, or read ahead for Part II.

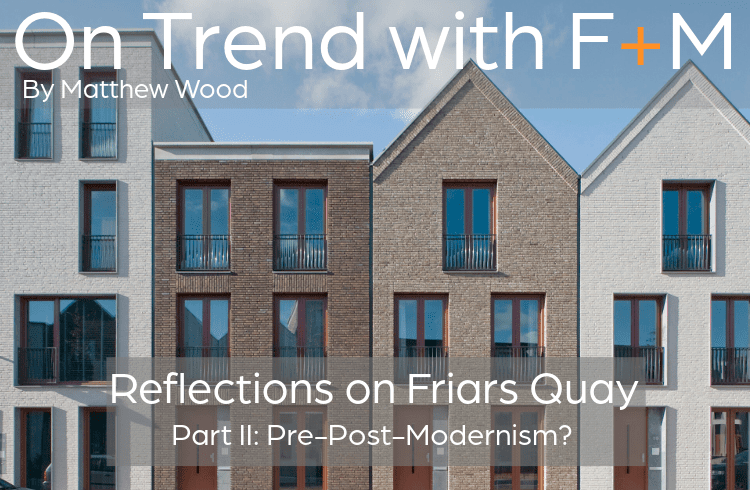

In 1989, Prince (now King) Charles expounded his ‘Vision of Britain’ and set UK housing design on a neo-traditionalist trajectory which it still largely follows, in terms of volume housing at least. In the years that followed this rupture, forward-looking young British architects sought residential work abroad (notably through the ‘Europan’ housing-design competitions) and eyed the Dutch Vinex housing-programme enviously across the North Sea. LEVS Architekten’s project at Leeuwenveld in Weesp (2005-2013) exemplifies a Dutch approach to housing-design firmly rooted in Modernism but with a growing awareness of history – and a sympathy towards it. The use of load-bearing brick in several different colours with punched, vertically proportioned windows, and on some buildings a row of pointed gables facing the street, all explicitly echo the materials and forms of Weesp’s historic town centre. But these are clearly modern buildings. They do not resort to the ‘fake old’ aesthetic of most UK housing – King Charles’s Poundbury, for example. The similarities between Leeuwenveld and Friars Quay are obvious, despite the two projects being separated by more than 30 years.

Left: Friars Quay, Feilden+Mawson, 1975; Right: Leeuwenveld, Weesp, LEVS Architekten (2005-2013)

Remarkably, the Architectural Review’s 1975 write-up of Friars Quay doesn’t even mention the use of different bricks on adjacent, otherwise more-or-less identical houses. Other features of the design were evidently too troubling. The author found the steeply pitched roofs overly ‘romantic’, evoking the silhouettes of the late mediaeval city rather than the ‘more accessible Georgian’ which formed the site’s immediate context. And they were also clearly troubled by the irregular stepping of the plan: ‘As set out on the ground the houses suggest the casualness induced by growth…One is pushed forward of its neighbour, another pushed back, another placed at a slight angle…(this is) the simulation of growth’.

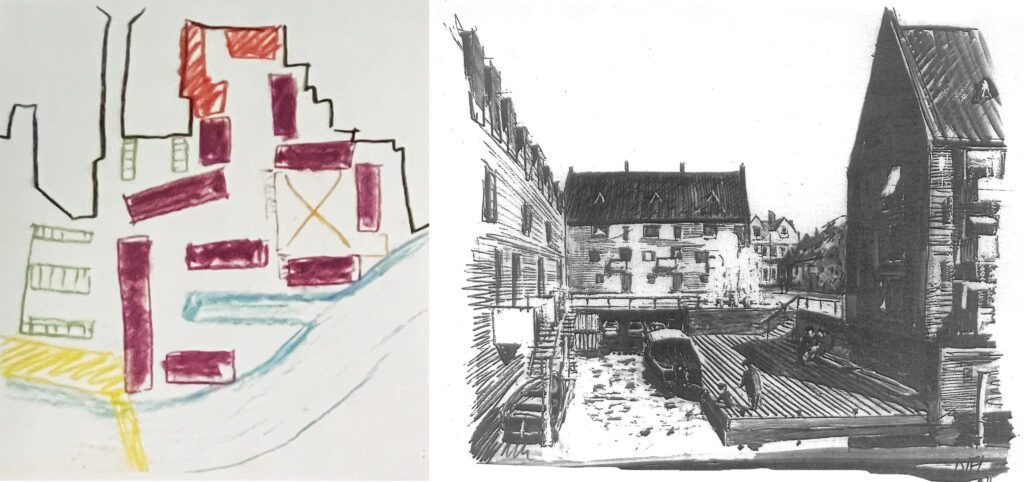

Over the course of this anniversary year we have renewed connections with Friars Quay’s very active residents’ association (of which, more later) and spent time with with F+M project architect David Luckhurst, now in his 90s but still spritely, engaged and happy to ‘talk shop’. On a walking tour of Friars Quay this summer I asked him where he got the ideas for the project. He replied (with a twinkle in his eye) ‘it came to me in a dream’, and waved a coloured crayon sketch at me. I arranged a follow-up session with him for further interrogation.

Design sketches by David Luckhurst.

Luckhurst was ‘trained as a brutalist’ at the Bartlett in the late 1950s and came to Norwich and Feilden+Mawson from his first proper job at Scott Brownrigg Turner in London. In 1963 he led the fast-track design and construction of the UEA ‘student village’ at Wilberforce Road, home to the new university’s first cohort of students while Denys Lasdun’s teaching wall and ziggurats took shape on the main campus. He then worked on several laboratory projects including the John Innes Institute, on what is now Norwich Research Park. When the Friars Quay project came his way in 1971 he was pleased, but surprised, not having previously done a substantial residential project…and then, understandably, he prevaricated. ‘Some early sketches were based on the UEA ziggurats’, Luckhurst confesses, ‘but it didn’t really work’. The date of the first client meeting loomed and (the story goes) the night before, the basic layout of Friars Quay came to him in a dream. He woke up, produced the sketch, and the meeting went really well. ‘But what of the steeply pitched roofs, the stepped plan, and the different coloured bricks?’, I asked.

Luckhurst suggests the steeply pitched roofs were a reference to the town houses of the Netherlands, which he had visited often. (His wife is Dutch). This feels appropriate given the long history of cultural transfer between the Netherlands and Norwich, which welcomed successive waves of weavers and then religious refugees from the Low Countries in the 16th and 17th centuries. He had also visited Venice on a number of occasions, and cites the verticality and multi-coloured brick and render of its townhouses as another possible source. But he recalls the main reason for the stepping in plan and the varying brick colour was more practical: the sales agent was insistent that buyers should be able to see individual houses on the site, despite the terraced format necessary to achieve the required density. (54 dwellings per hectare in the final scheme).

It would be interesting to see how these ideas would have developed on future projects, but after Friars Quay Luckhurst was called back by F+M to designing laboratories and education buildings. He only completed one other residential project – which he says he would ‘rather not talk about’! A number of other F+M residential projects in Norwich from around this time made similarly interesting responses to their historic context, though these were led by partner Simon Crosse, who died in 2021. I hope to return to these in later posts, but looking back it feels there was an architectural ‘moment’ in Norwich in the early 1970s – including the end of David Percival’s tenure as City Architect – which is not yet well documented. As a footnote in our interview Luckhurst was keen to give credit to city planner Alfie Wood who championed good design and conservation in the city from the mid-1960s, including the pioneering pedestrianisation schemes on London Street and around Unthank Road.

So, looking back it doesn’t seem reasonable to claim that Friars Quay was influential on the main streams of architectural design in the UK as a whole.

The month before its coverage of Friars Quay, the October 1975 issue of the Architectural Review featured Norman Foster’s revolutionary and influential glass-clad office building for Willis Faber Dumas in Ipswich, which heralded the start of the British ‘high-tech’ movement. And when the ‘post-Modern’ thinking of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown eventually filtered into British residential projects by the likes of Jeremy Dixon, Piers Gough and Richard MacCormac in the late 1970s and early 80s, the emphasis was on the literal and exuberant quotation of historical motifs – classical columns, arches, crow-stepped gables and polychromatic brickwork. The lower-key ‘resonant’ response to history and context signposted by Friars Quay didn’t really emerge until a second wave of post-modern innovation in the early 2000s – typified, perhaps, by Leeuwenveld. In this context Friars Quay is a project that looks 30 years ahead of its time, and still remarkably fresh today.

Click here to read Friars Quay Part III, ‘Shared Streets, Squares & Alleys’ which looks in more detail at the layout of the development, and the design and management of its public spaces.

By Matthew Wood, Senior Architect at Feilden+Mawson